Data Contracts: A Missed Opportunity

The Conversation We Should Have Had—Before Thought Leadership Replaced System Design

Over the last couple of years, the data industry has been having a conversation about data contracts that never quite went where they needed to.

There was no shortage of activity around the topic. Definitions were proposed and refined. Conceptual boundaries were drawn and redrawn. Data contracts were compared to APIs, governance frameworks, data mesh primitives, and ideas teams already “sort of” implemented in practice.

The discussion was energetic and well-intentioned, but it tended to stay at the level of classification rather than construction.

What was largely absent was sustained engagement with the engineering consequences of taking data contracts seriously. Questions about enforcement, evolution, compatibility, and failure modes appeared only briefly before the conversation moved on. The result was an industry consensus that data contracts were “interesting,” without a shared understanding of what it would actually mean to build platforms around them.

In hindsight, this matters—not because the debate was unproductive, but because of what happened in parallel.

The Shift Happening Elsewhere

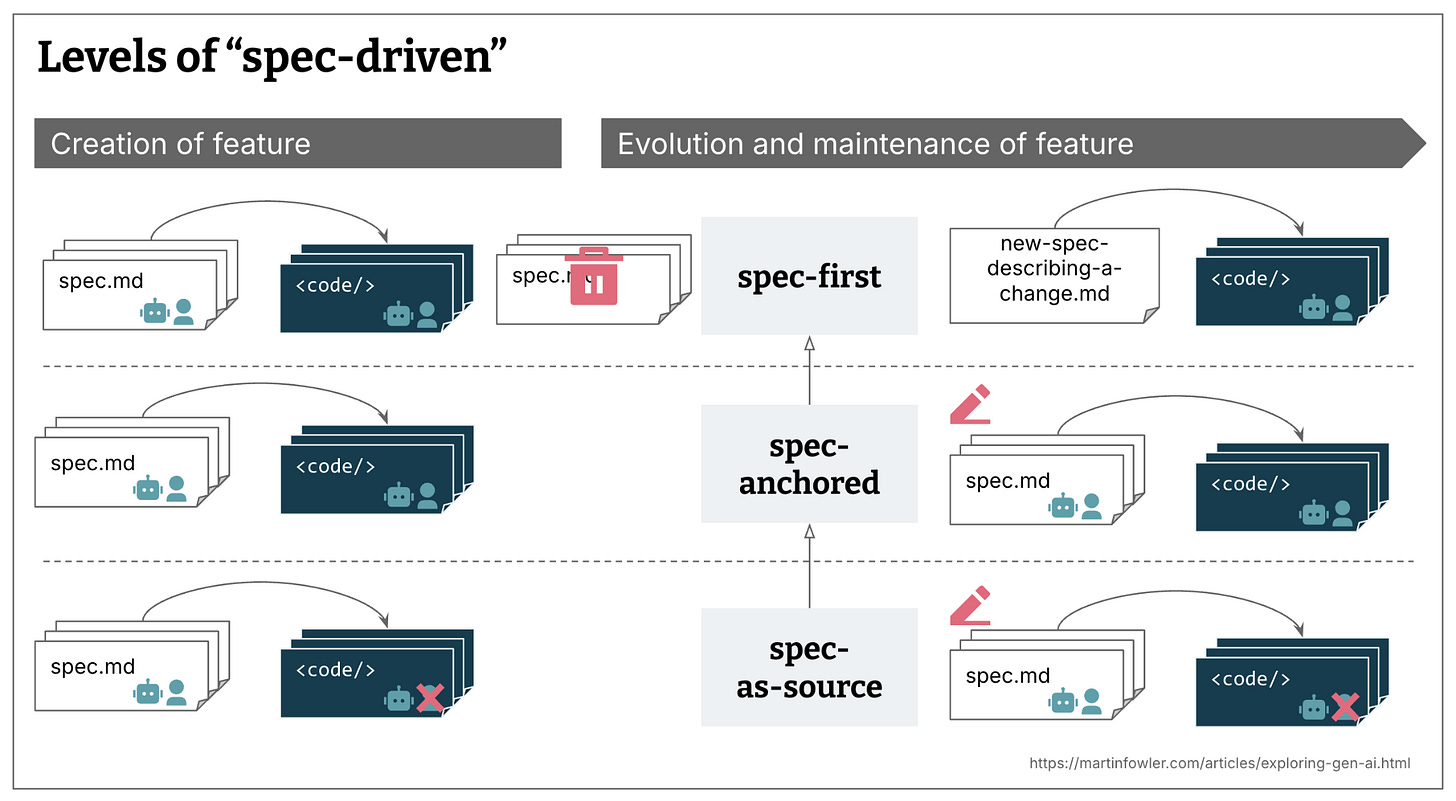

While the data community was debating what data contracts were, the software engineering world was converging—quietly and pragmatically—on a different organizing principle: specifications as the primary unit of system design.

This wasn’t a philosophical shift so much as an operational one. As systems became more distributed, more automated, and more interdependent, informal agreements stopped scaling. Documentation drifted. Assumptions diverged. Human coordination became the bottleneck.

The response was not more process, but more precision.

APIs began with schemas rather than code. Infrastructure moved from scripts to declarative specifications. Compatibility rules were automatically encoded and enforced. In these systems, the specification was no longer an artifact produced alongside the system—it was the system.

More recently, AI agents have accelerated this trend. Agents do not operate on intent, convention, or context. They operate on explicit, machine-readable, and verifiable data. Where specifications exist, agents can reason deterministically. Where they do not, agents approximate—and approximation is rarely acceptable in core infrastructure.

This is where the connection to data contracts becomes unavoidable.

Data Contracts as Specifications, Not Concepts

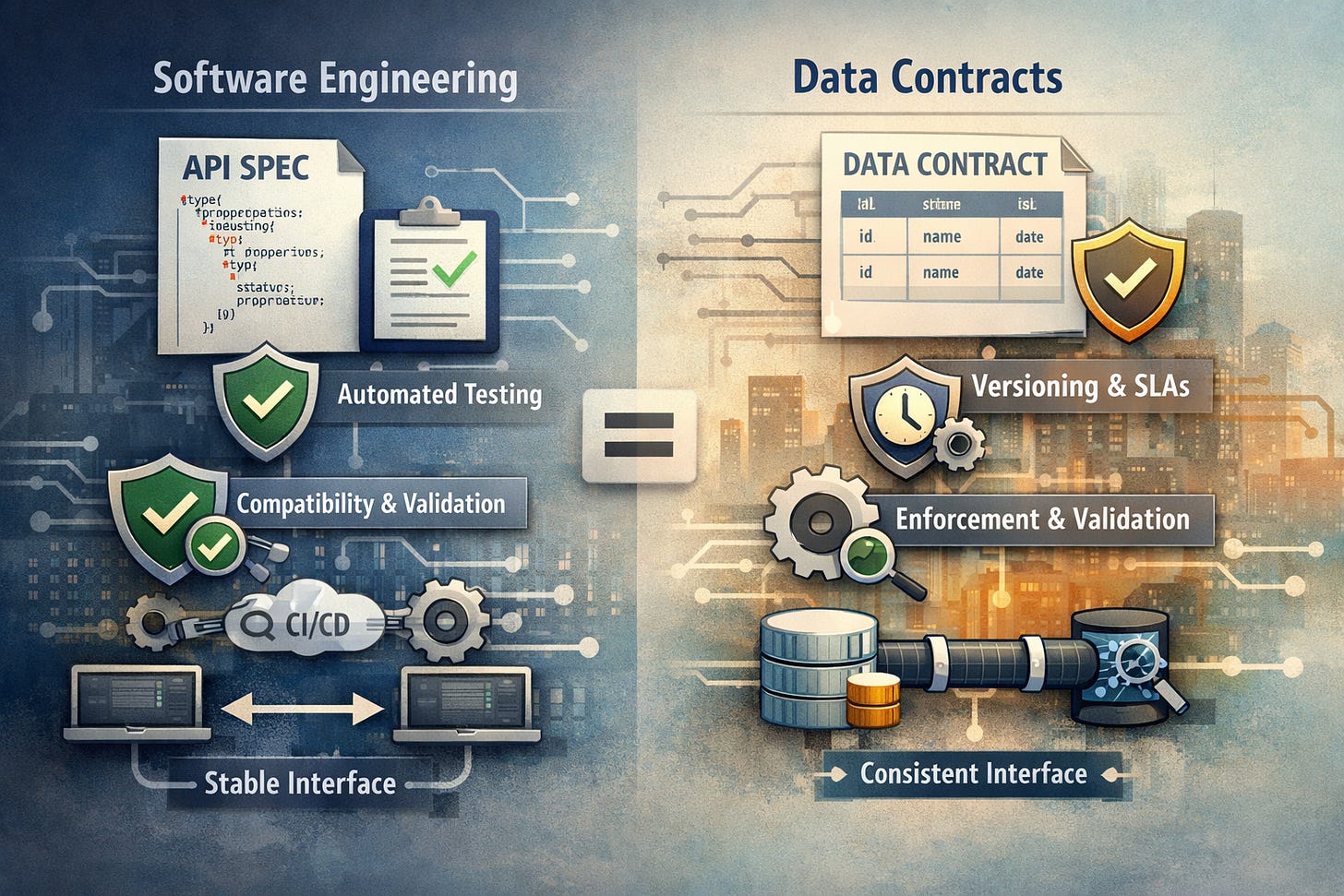

Viewed through the lens of spec-driven development, data contracts stop looking like a data-specific innovation and become a familiar pattern applied to a different domain.

A properly implemented data contract is a specification:

It defines structure, semantics, and invariants

It establishes compatibility guarantees over time.

It is versioned, validated, and enforced programmatically.

It creates a stable interface between independently evolving systems.

This is exactly what spec-driven development has optimized for in software engineering.

The difference is not conceptual—it is operational. Software engineering treated specifications as executable constraints. The data industry often treated contracts as descriptive artifacts. As a result, contracts were discussed as governance tools or communication mechanisms, rather than as interfaces with failure semantics.

That framing limited how far the idea could go.

Where the Two Worlds Diverged

Spec-driven systems force early clarity around hard problems.

How does change propagate?

What is allowed to evolve independently?

What breaks compatibility, and how is that detected?

Where does enforcement occur, and what happens when it fails?

In software systems, these questions are answered in code and tooling. In data systems, they were often answered socially. Producer–consumer agreements existed, but they lived in tickets, meetings, and tribal knowledge rather than in executable form.

Many teams compensated by building partial solutions: strong schemas, upstream quality checks, and informal SLAs. These patterns worked, but they relied heavily on human intervention. They were resilient, but not legible to machines.

As long as humans were the primary integrators, this was manageable. As soon as AI agents enter the workflow, it becomes a constraint.

Why Spec-Driven Thinking Changes the Next Phase

AI agents make an implicit demand of data platforms: make your rules explicit.

Agents can generate schemas, propose transformations, reason about compatibility, and enforce policy—but only if the platform exposes contracts in a form they can execute against. Without that, agents revert to inference, which introduces uncertainty precisely where determinism is required.

This is the practical implication of spec-driven development for data engineering. It’s not about adopting a new paradigm. It’s about recognizing that the platform already behaves like a system of interfaces—and formalizing those interfaces accordingly.

Teams that have already internalized contract discipline will find this transition incremental. Teams that have not will experience it as friction.

What We Should Do Next

At this point, the terminology matters less than the mechanics.

Whether we call them data contracts, data interfaces, or executable schemas, the path forward is the same:

Treat schemas as specifications, not documentation

Encode quality, semantics, and compatibility as executable rules

Enforce contracts at clear system boundaries, preferably early.

Version data interfaces with the same rigor as APIs

Make ownership and accountability explicit and machine-readable.

This is not about adding process. It is about making systems legible to other systems.

Closing Thought

The original data contracts conversation wasn’t wrong. It just stopped too early.

Spec-driven development has shown that explicit, enforceable interfaces are not optional in complex, automated systems. Data platforms are now at that same inflection point.

Data contracts were never the destination.

They were the missing layer that would have made everything else easier to build.

The opportunity is still there—but only if we’re willing to treat contracts as infrastructure, not ideas.

References

https://www.thoughtworks.com/insights/podcasts/technology-podcasts/data-contracts-what-why

https://airbyte.com/data-engineering-resources/data-contracts

https://soda.io/blog/what-are-data-contracts

https://atlan.com/data-contracts/

Nice article, thanks for sharing. I agree it’s a missed opportunity, or at least missed by *some*, as this is exactly how we implemented data contracts (https://medium.com/gocardless-tech/implementing-data-contracts-at-gocardless-3b5c49074d13), and is how I’ve always talked about it, including in my book (https://data-contracts.com).

I think what’s happened is people started rebranding existing features of their platforms as data contracts, to ticket a box, and that drowned out the original premise of data contracts.

So it’s great to see you publish this reminder, and hopefully restart the discussion on how data contracts can be the driver of the data platform.

Take a look at DataSurface, I think it's the worlds first closed loop contract based system, spec driven... www.datasurface.com, I have had this argument with modelers for a while now. A model that is not implementable is for generating wall paper. I tend to focus on automating a set of patterns through one or more implementations. Patterns like production of data, consumption of data, materialization of existing data. Once we have consumers with specs, we can choose the best available implementation and get end to end automation.